Elvin Ray Jones (drummer) was born on September 9, 1927 in Pontiac, Michigan and passed away on May 18, 2004 in Englewood, New Jersey at the age of 76.

Elvin Jones was born to parents Henry and Olivia Jones who moved to Michigan from Vickisburg, Mississippi. His father was a lumber inspector for General Motors who sang bass in the church choir. Elvin’s mother, a homemaker, raised a total of ten children, of whom Elvin was the youngest. Two of Elvin’s older brothers are also jazz musicians: Hank, a pianist, and Thad, a trumpeter and arranger.

As a child, Elvin was exposed to gospel, blues, and jazz through both his parents and older siblings, and his musical talents became evident at a very young age. By his early teens, Elvin was already drumming in the style of his early influences, Jo Jones and Shadow Wilson. Jones began service in the United States Army in 1946. He was discharged in 1949, and returned home penniless. Jones said he borrowed thirty-five dollars from his sister when he got back to buy his first drum set.

He immediately immersed himself in the rich Detroit jazz scene. Billy Mitchell, a tenor saxophonist and bandleader, soon hired both Elvin and Thad Jones to play at the Bluebird Inn, where they backed jazz legends such as Charlie Parker, Sonny Stitt, Wardell Gray, and Miles Davis during their three-year stint there.

After this successful run in Detroit, Jones moved to New York in the mid-1950s. He was undeterred by his unsuccessful audition to join Benny Goodman’s group, and remained in New York, where he freelanced with almost all of the era’s leading names, including Charles Mingus, Bud Powell Gil Evans, J.J. Johnson and Miles Davis.

Elvin’s most famous early recording came from a run of dates with Sonny Rollins at the Village Vanguard in November of 1957. Rollins and Jones performed only with a bassist, and the lack of chordal accompaniment forever altered the scope of improvisational possibilities between the drummer and soloist in modern jazz. I Can’t Get Started and Old Devil Moon are fine examples of the interaction between the two musicians.

In 1960, Jones joined John Coltrane’s now ‘classic’ quartet. The perfect foil for Coltrane’s musical personality, the pair developed a virtually telepathic relationship in which they anticipated every intense climax or rhythmic motive.

Highlights from Jones’s tenure with Coltrane include their Latin-to-swing version of The Night Has A Thousand Eyes, Chasin the Train and Spiritual (B) from their performances at the Village Vanguard in 1961.Other crowning achievements with Coltrane is A Love Supreme, and a master-class in sustained intensity from a 1965 recording at the Half Note, entitled One Up, One Down.

During his nearly six years with Trane, Jones also freelanced and appeared on some of the sixties’ most memorable tracks, such as Dance Cadaverous on Wayne Shorter’s Night Dreamer, and Inner Urge on Joe Henderson’s Inner Urge.

Elvin began recording as a co-leader with increasing regularity in the 1960s. Successful collaborations in the late 60s included a session with bassist Richard Davis entitled Heavy Sounds (1968), and a semi-regular trio with tenor saxophonist Joe Farrell and bassist Jimmy Garrison that can be heard on Puttin’ It Together (1968).

Jones spent much of the 1970s recording as a leader as well, including sessions with a young Dave Liebman from the Lighthouse Club in California and an octet recording with Clark Terry and James Moody entitled Summit Meeting (1976). The late 70s saw Jones collaborate with altoist Art Pepper, under Jones’ name (Very R.A.R.E., 1978) as well as under Pepper’s name (The Complete Village Vanguard Sessions, 1977).

Jones’s final act was to form the Jazz Machine, a revolving door of jazz musicians that released its first recordings in 1978. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the band toured and released records, many of them capturing the group live in concert. These records featured, in different combinations, musicians Frank Foster, Roland Prince, Pat LaBarbera, Sonny Fortune, Richard Davis, Nicholas Payton, Javon Jackson, Brad Jones and Ravi Coltrane. The Jazz Machine continued touring and recording until Jones’s death from heart failure in 2004.

Jones and Nagasaki native Keiko Jones were married in 1966, and remained married until his death. Keiko acted as his personal and business manager, and also arranged and composed charts for the Jazz Machine. Jones is survived by one son, Elvin Nathan Jones, of California, and one daughter, Rose-Marie Fromm, of Sweden.

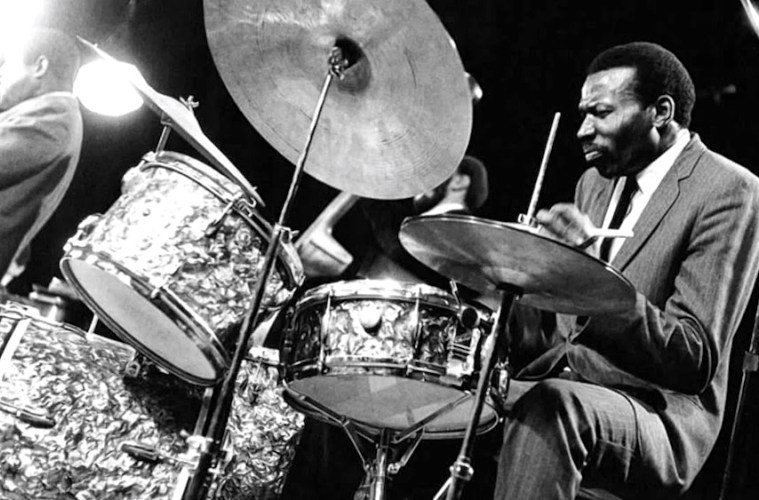

Jones left an indelible mark on jazz drumming. His style summed up the accomplishments of his predecessors – Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Jo Jones and Max Roach – yet he gave the drums a speaking voice that was entirely his own.

His prodigious technique, four-limb independence and penchant for polyrhythmic invention were coupled with a thunderous intensity He occasionally shifted ride-cymbal accents from the downbeats of to the upbeats of beats two and four were revolutionary and copied by nearly every subsequent jazz drummer.

Jones’s ability to remain musical and tasteful at a thunderous volume pushed his collaborators to new musical heights, and made him a favorite of soloists as well as fellow drummers. Jones has been inducted into the Halls of Fame of the Percussive Arts Society, Modern Drummer, Downbeat Critics Poll, and Zildjian.